Downloads

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7480/rius.6.97Keywords:

landscape architecture, inclusive urbanism, generous cities, education, perception, palimpsest, process, scale-continuumAbstract

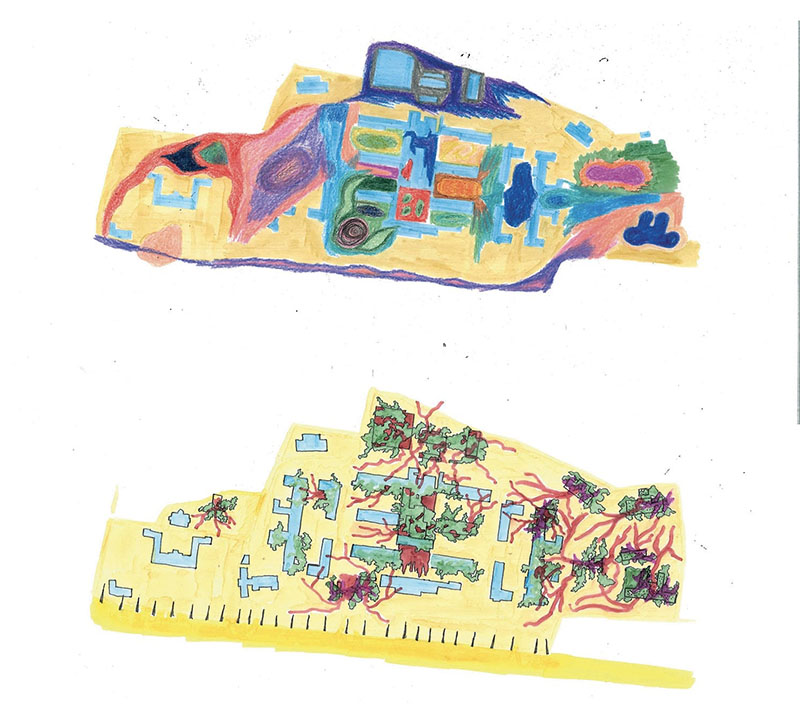

Landscape architectonic compositions that draw on the underlying landscape structure can function as a carrier for changing programmes, cultures, processes, etc. Precisely such an explicitly spatial design is required to foster the inclusive city, one that is not only socially just but also sensitive to the environment while allowing for and evoking diverse social and natural processes. The objective of an ‘inclusive city’ is often related to social issues, which might easily lead to the exclusion of ecological values; the opposite approach may prove equally exclusive. Inclusivity also means creating room for the unexpected. From a design point of view, this requires two underlying attitudes: a willingness to see any design assignment from different perspectives as well as a readiness to create sustainable, flexible and open designs.

These two attitudes are inherent to landscape architecture, which traditionally prioritizes the site over the programme, and—because of the long term, time-based condition of the landscape—is forced to think in open-ended designs. In this paper we discuss a selection of graduation projects of the landscape architecture track at the TU Delft in order to illustrate how inclusivity is inherent to a complete understanding of landscape architecture. Four essential perspectives on analysis and design—perception, palimpsest, process and scale continuum—are discussed in order to reveal their capacity to serve as a basis for designing inclusive urban landscapes.

How to Cite

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2020 Inge Bobbink, Saskia de Wit

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

De Block, G., Lehrer, N., Danneels, K., Notteboom, B. (2018). Metropolitan Landscapes? Grappling with the urban landscape design. SPOOL, 5 (1), 81-94. doi: 10.7480/spool.2018.1.1942.

Braae, E. (2015). Beauty redeemed. Recycling post-industrial landscapes. Birkhäuser.

Burns, C., & Kahn, A. (2005). Site matters: Design concepts, histories, and strategies. Routledge.

Cache, B., & Speaks, M. (1995). Earth moves. MIT Press.

Van Etteger, R. (2015). Tijd. In H. Dekker, M. Horsten, M. Kok (Eds.), Duurzame landschapsarchitectuur (pp. 220-225). Uitgeverij Blauwdruk.

Gibson, J.J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin.

Halprin, L. (1970). The RSVP Cycles. Creative processes in the human environment. George Braziller.

Jauslin, J. (2012, September). Landscape design methods in architecture [Paper presentation]. Landscapes in Transition, 49th IFLA World Congress Cape Town South Africa.

Marot, S. (1999). The reclaiming of sites. In J. Corner (Eds.), Recovering landscape: Essays in contemporary landscape theory (pp. 45-57). Princeton Architectural Press.

Meyer, E. (1997). The expanded field of landscape architecture. In G.E. Thompson & F. Steiner (Eds.), Ecological design and planning (pp. 167-170). John Wiley & Sons.

Nijhuis, S. (2013). Principles of landscape architecture. In E. Farini & S. Nijhuis (Eds.), Flowscapes. Exploring landscape infrastructures. Universidad Francisco De Vitoria.

Prominski, M. (2004). Landschaft entwerfen. Zur Theorie aktueller landschaftsarchitektur. Berlin Reimer.

Smith, C. (2017). Bare Architecture. Bloomsbury.

Van der Velde, J. R. T. (2018). Transformation in composition: Ecdysis of landscape architecture through the Brownfield Park Project [PhD dissertation]. Delft University of Technology.

Voorthuis, J. (n.d.). De mogelijkheid van een genereuze stad. Een oefening in het denken over het lachen en de beleefdheid. http://www.voorthuis.net/Pages/Een%20genereuze%20stad_jctv.pdf